The ability to recognize opportunities and move in new - and sometimes unexpected - directions will benefit you no matter your interests or aspirations. A liberal arts education is designed to equip students for just such flexibility and imagination. --Drew Gilpin Faust, American Historian

Last night, I was hanging out at my favorite local watering hole, and I met my friend Matt, who introduced me to his friend, Jill, a beautiful, vibrant woman who happens to date one of the watering hole's employees. The three of us got into an elaborate and funny conversation about the differences between "nerd" and "geek."

My own view is shaped by my having come of age in the 1970s, when nerd meant something very specific, and it wasn't a compliment. I was constantly called a nerd as a kid, I guess because I liked school and got good grades or maybe because I kind of looked/look like a nerd!

The word "geek" didn't even really appear in my experience until the 1980s and always seemed to have more of a connotation of a person having a particular idiosyncratic interest that goes way beyond what's typical.

The three of us went back and forth and all around, eventually lapsing into a kind of punchy silliness in which each of us tried to use "nerd" or "geek" in some new way that illustrated the different ways they can be used. Jill made perhaps the best point of the discussion, which is that the definitions of these terms are quite fluid and you don't really know what someone means by their use of one or the other unless you look at the context and sometimes even then you have to ask for some elaboration. We three agreed that equivocation about the meaning of "nerd" and "geek" was the better part of wisdom.

But that's not what I want to write about today. As the nerd vs. geek discussion wound down, we began discussing the particularly nerdy (or geeky) quality in some people that they are really interested in some particular area of study, often not very practical. Jill expressed a somewhat negative view of people who study, for example, sociology in college, as if that might prepare them for some sort of practical job afterwards. I pressed her on this a bit, because it seemed to me that she was saying that it's a mistake for people to study a discipline like that in college--that college should have some relationship to getting a decent job afterwards. "You know how many people with B.A.'s in the liberal arts are working in places like this as waiters and waitresses?"

As people who know me can attest, I often find myself defending a point of view that goes against what is taken to be "conventional wisdom." This notion that going to college and majoring in the liberal arts is impractical and in fact somewhat idiotic given the realities of the current economic climate is one of those conventionally accepted ideas that I consider to be worthy of ongoing critique.

It turns out that Jill is a professor of social work, which might explain why sociology was her particular choice of an impractical college major. Whereas sociology at the undergraduate level is full of grand theories that don't have much particular application to the actual concerns of actual people in actual situations (or so Jill's sense of it goes), social work is a real profession, and those who study social work are initiated into a whole set of practices, useful theoretical frameworks, and standards that ensure that it connects directly to the real world.

I myself majored in history in college, and I think I've done quite fine by myself (thank you very much). Yet getting a job in 1983 when I graduated was no cake-walk, for sure. (Like many of my liberal-arts-educated friends, I went to law school, which was supposed to ensure that I would get a great job, make a lot of money, and be eternally happy. It didn't quite work out that way, but that's a story for another time.) Now I work as a professor in the field of education, which, like social work, has a similar kind of existential connection to the real world that keeps it from being the province primarily of academic nerds. (This is not to say there aren't education nerds, but they are a lot more rare than, say, sociology nerds. People don't tend to go into education out of a purely theoretical interest. If the standard response that an education major got when she revealed her choice of major at a cocktail party was "What are you going to do with that?," many of us education professors--especially those of us with a primarily theoretical interest--would be out of a job.) So I get what Jill was trying to say about the difference between majoring in something like sociology--with little practical application--and social work--which is nothing if not practical.

But I'm a nerd, and I get a particular nerdy kick out of being particularly contrarian about what I see as too-likely-to-be-accepted-without-question conventional wisdoms like "it's not smart to go to college and major in something like sociology and expect to find a job afterwards."

Without necessarily being aware that she was playing a role in a more common morality play, Jill hit all the right notes in the ensuing conversation. She even started getting emphatic about her main point when I began pushing back.

You always know someone is getting emphatic about something when they start using this "illustrator" gesture:

This gesture is less threatening than a "tomahawk chop" through the air, but it is used to "indicate decisiveness, chopping with each point." When someone starts emphasizing their point with this gesture, I'm always tempted to mimic them, to show them the effect of their gesture. Sometimes, it gets people to realize that their gesture may indicate that they're passionate about what they're saying, but the gesture does little to convince someone else.

Jill's point was that going to college and majoring in the liberal arts is not only impractical but even idiotic. "Everyone [hand chop] knows that it's nearly impossible [hand chop] to get a job [hand chop] out of college with a liberal [hand chop] arts {hand chop] major [hand chop]."

"But not everyone knows that!," I interjected. "And it's not even true! Lots of people get good jobs after going to a place like the University of Chicago with a liberal arts major!"

"But that's not the point," she chopped. "The world has changed! It's no longer the case that having a liberal arts degree identifies someone as an elite person with enormous potential in a job!"

"But it's true for some people!"

"But it's not true for most!"

"But that doesn't mean people shouldn't do it!"

"They shouldn't do it if they expect to get a job!"

At this point, we paused. She was clearly frustrated that I wouldn't admit a simple empirical point about the changing value of a liberal arts degree. I was frustrated that she seemed to believe that her "empirical point" was more important than the circumstances of an individual person's life choices.

As we briefly debriefed what had just happened, I realized that she was expressing a more-or-less typical social worker position that tries to help people make good choices by clewing them into the larger context of those choices, whereas I was expressing a philosophical, existentialist position that each individual's choices are unique, with specific unique circumstances that are far more important in determining outcomes than empirical generalizations. As Jill put it, we were "having different conversations," which is why we weren't coming to agreement but just clinging more strongly to our positions.

So what to make of all this?

First, let's look at the claim that a liberal arts degree isn't worth what it used to be. Turns out that this claim, while widely held, is harder to prove than it might seem.

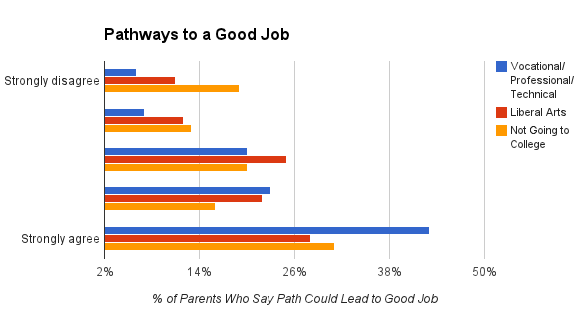

How widely held? In 2012, Gallup surveyed parents of pre-collegiate students and found that more parents believed that majoring in a vocational/professional/technical degree was likely to result in their children getting a good job than those who believed a liberal arts degree would, and in fact, that more parents thought not going to college at all would result in a good job than parents who thought going to college and majoring in the liberal arts would:

(That study also showed that more parents identify getting a good job as the most important reason to go to college than becoming a well-rounded person.)

Conservative pundits and politicians seem particularly likely these days to criticize the liberal arts. Part of the reason for this seems to be an underlying distrust of the the focus of some liberal arts subject-matter on examining power relations and the history of oppression of certain groups, such as gender studies does with regard to women. The humanities seem to have a particularly bad rap in terms of how people think of their value as a college major. One "study" (more like an opinion piece with a right-wing bias) claims that the following majors are "useless" and "do jack sh** for you in the real world": art history, philosophy, American studies, music therapy, communications, dance, English literature, Latin, Film, and religion. But criticisms of the liberal arts aren't confined to conservatives; even Robert Reich, Democrat and former Secretary of Labor, believes more students should choose technical degrees rather than liberal arts.

A Pew study released in early 2014 found that graduates who had majored in the liberal arts, social science, or education were more likely than those who had majored in science and engineering to express regret about their choice of major (33% to 24%). The former group is also much more likely to say that they are overqualified for their current job (42% to 28%). Graduates who majored in science, engineering, or business are also more likely to believe that their college major is closely related to their current job.

Interesting, Millennials are more likely than Baby Boomers to express some regret about their choices in college, including their choice of major. This gives some tangential support to the notion that things are changing in terms of whether majoring in the liberal arts is something people come to regret later. However, it could also be the case that Baby Boomers have had a longer time since college to come to terms with their choices or find some way to make those choices work for them.

Further evidence of a change in the value of the liberal arts comes from educators and administrators who work in higher education. David Maxwell, outgoing president of Drake University, writes that "Thirty years ago, it was fairly risky for an academic at a liberal arts college to talk among colleagues about the 'relevance' of liberal education to the real world, especially to preparing students for employment." But that has changed; everyone in higher education now recognizes that dealing honestly and up front with issues of relevance and job prospects is necessary to make the case that parents and students should invest time and money in a college degree of any type.

What about employers' perceptions? Certainly they want to hire people with the technical skills they need for particular jobs. And according to some employers and economists, there is a shortage of skills in many technical fields, whereas there seems to be a surplus of those with liberal arts majors.

According to one study, only 2% of employers are seeking to hire graduates in the liberal arts, whereas 27% want engineering and computer science graduates, and 18% want business majors.

However, the number one "job skill" that employers want in their new hires is a strong work ethic. They also want adaptability. As some researchers have written, "The modern workplace demands adaptability, broad-mindedness and creativity -- competencies that are well developed in programs based on a liberal or general education model." Critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication skills are developed by rigorous participation in disciplines across the liberal arts.

But what of the bottom line? Does majoring in the liberal arts hurt the prospects of college students in terms of salary?

Well, yes. Recent college graduates with liberal arts degrees tend to make less money than those who majored in professional or preprofessional fields, or in the sciences, math, or engineering. One study concluded that the college majors with the lowest overall financial return on investment (ROI) are, beginning with the lowest: Communications, psychology, nutrition, hospitality/tourism, religious studies/theology, education, fine arts, and sociology. (Only some of these are what is traditionally thought of as "liberal arts.) This echoes what career advisor Penelope Trunk says, that 85% of college students are wasting their money. (Trunk doesn't specifically criticize the liberal arts, saying that what really matters is the quality of the school rather than the major. More on this, below.)

Liberal arts majors do tend to make up this ground over time, earning more during their peak earning years (age 56-60) than the professional or pre-professional majors. However, this advantage of the liberal arts disappears when those who have gone on to get advanced degrees are taken out of consideration. What's more, those who majored in science, math, or engineering end up making considerably more ($20 - $30K per year) than those who majored in the liberal arts. (See the report details here.)

So majoring in the liberal arts is likely to result in lower earnings overall during a career than majoring in science, math, or engineering. The unemployment rate among recent liberal arts graduates is also slightly higher than it is for science majors. Does this mean hand-chopping Jill was right?

Certainly there are financial premiums for majoring in science, math, or engineering (the so-called STEM fields). But there's no evidence that majoring in a professional or pre-professional field (like social work or education) is better than majoring in the liberal arts, at least not financially, and certainly not over the long haul.

Some have argued that the advantage of the STEM fields isn't so much the particular subject matter that is studied, but the ways that this subject matter is taught, in a practical and applied manner. As Boston's Northeastern University President Joseph E. Aoun recently writes, "liberal arts classes are often framed by the traditions of the essay and exam paper." This makes them more likely to stress abstract concepts.

"This boundary between the abstract and the real may largely account for the conceit that a liberal arts education doesn’t equate to a tangible outcome, or a tangible paycheck. However, liberal arts programs can counter this misperception by reproducing the lessons from engineering laboratories or business school co-op programs and adding an experiential component. By practicing the experiential liberal arts, they would better prepare their students to engage in the world."Aoun, whose university has pioneered a cooperative approach to undergraduate education involving partnerships with businesses and nonprofit organizations, urges liberal arts programs to incorporate applied experiences such as internships and community service programs. The tendency to draw sharp contrasts between "applied" work such as that in the sciences and more theoretical work such as that in the liberal arts is, Aoun suggestions, a false dichotomy.

"Every scientist needs to ponder the context of her work and communicate its meaning; every liberal arts student should wrangle with the revelations of big data. Both applied disciplines and the liberal arts have much to share between them. By bleeding a little into each other, these two approaches to higher education would give every graduate a powerful, marketable education for today’s economy.

"So let’s move past the false dichotomy that characterizes the current debate over the liberal arts and applied disciplines. Better to draw lessons from both, and agree that the most valuable education is one that works."Another less dichotomous way of thinking is for liberal arts majors to take advantage of the flexibility that many of their programs offer for taking electives.

“In the current economy, majoring in liberal arts won't yield good job prospects, so you have to pair a liberal arts degree with business [or marketing, or operations] courses in order to become a more appealing candidate,” said Dan Schawbel, founder of Millennial Branding.Schawbel also found that for some employers, a candidate with no college degree--but real world experience--is more attractive than a typical liberal arts graduate who hasn't really done anything practical. What really matters isn't so much the degree as positive attitude, communication skills, and an ability to work well on a team, especially one with diverse participants.

However, the combination of the liberal arts with more practical and applied subjects--especially when coursework is supplemented by real-world experiences--may be the best of both worlds. The liberal arts have value for helping people across many fields to ask good questions and think through difficult problems--skills that potentially have enormous payoff. Some colleges are experimenting with hybrid courses and majors that aren't easily characterized as "liberal arts" or something else.

So much for the point that Jill was trying to make. She's clearly wrong that majoring in the liberal arts is a poor choice for young people today, or that majoring in professional or pre-professional fields is a better choice. In general, students may do better financially and in terms of getting immediate post-graduate employment if they major in STEM fields, but that's simply not a choice that every person can make.

But everything I've brought into this debate up until this point suffers from the fact that these are generalizations: they capture what is true overall, on average, in general. Do they determine what will happen in any individual's life?

I think the answer to that question is no. Individuals make choices. Sometimes those choices have consequences. Sometimes those consequences can be vaguely predicted from what is true in general. But not always. Maybe not even usually.

This idea that what happens to each of us in life is a result of how our choices fit into the percentages of the larger population (usually determined using samples, sometimes of sufficient size to make identify significant differences) is fundamentally flawed. Yes, in general a recent college graduate is slightly more likely to find a job immediately after graduation if he or she majored in a STEM field. But the difference is relatively minor and more field-specific than determined by the broad categories of STEM vs. liberal arts. A 2013 report found the unemployment rate among recent college graduates was lowest in nursing (4.8%) and elementary education (5.0%), followed by physical education/recreation (5.2%) and then chemistry (5.8%) and physics (5.9%). Having a professional major, then, is more likely to get someone a job immediately following graduation--more likely even than majoring in pure science fields. But the highest unemployment rate among recent graduates is in the field of information sciences (14.7%), followed by architecture (12.8%), neither of which is considered "liberal arts." Indeed, one of these is a STEM field, and the other is a professional field. So the generalizations at the level of "STEM" and "liberal arts" don't even hold true once we get more specific and look at majors in specific subjects.

This illustrates a general point about generalizations: while they may hold true "in general," they begin to break down as soon as more specific categorizations enter in. (These things also change over time, and not always in one direction. Liberal arts graduates, for example, seem to fare better during times of economic growth.)

So, yes, majoring in sociology carries a higher risk of unemployment immediately following graduation from college (9.9%) than does majoring in social work (8.2%). (This ignores the fact that one of the most likely career choices of sociology majors is social work.) But what does this mean for the individual?

Let's get real here. If 100 people who majored in sociology are looking for a job, 9.9% of them might fail to find one. If 100 people who majored in social work are looking for a job, 8.2% of them might fail to find one. But does this mean than any given person is only 98.1% as likely

(((100-9.9)/(100-8.2))*100%) or (90.1/91.8)*100%

to find a job immediately after college if they major in sociology vs. social work? And how significant is that 1.9% difference, really?

Here's the thing: the categories "sociology major" and "social work major" are very crude characterizations. For one thing, they ignore the influence of gender, race, GPA, specific courses taken, the quality of recommendations, who the student (or his family) knows, and the specific school that they graduate from! Could it be that THESE categorizations, or qualities, are more important than college major in determining who gets a job right out of college?

The specific school matters quite a lot, which supports Penelope Trunk's advice to maybe skip college unless you get into a top school. 96% of graduates from the University of Chicago, for example, are employed or in graduate school within 6 months of graduation. While students' specific major might matter, simply graduating from the University of Chicago gives someone a huge leg up over graduating from a less elite school such as

I believe that we have a tendency in our culture to take data as determinative of what will happen. But data isn't reality! It is simply a numerical or categorical representation of the reality that is encompassed by our measures or categories.

Hunter Rawlings III, president of the Association of American Universities, makes a similar point, using the example of James Madison, one of the most important contributors to the US Constitution.

Madison, Rawlings reminds us, returned home after spending his undergraduate years (and one graduate year) at Princeton, without a job and with few prospects. His studies of the Classics did little to given him the specific skills necessary for a trade or occupation. He was unemployed for two years, and would have shown up in data as having made a bad choice of college major. However, when the American Revolution broke out, Madison was poised to become a great statesman and leader. The data would have characterized him very differently in 1809, when he became the fourth President of the United States.

The liberal arts have the capacity to expand a students' consciousness of sometimes hidden realities such as the importance of power in human relationships, the aesthetic qualities of seemingly technical situations, intuitions into the perennial spiritual questions that all humans face, and the ways that adversity can generate a range of human responses. No one knows when these capacities might be helpful to a person. Perhaps those with a background in the liberal arts are more adaptable or flexible in the face of enormous social change. The liberal arts train students to thrive in subjectivity and ambiguity, a necessary skill in the tech world where few things are black and white.

But again, these general truths about the value of the liberal arts don't matter nearly as much--indeed, they matter little at all in comparison--as the specific ways that educational experiences affect the outlook, thinking, and habits of a particular person. Each of us is unique. The consequences of the choices each of us make will be unique. What matters to each of us is unique.

Jessica Kleiman gives what I consider pretty good advice:

"Do what you love, study what interests you, get good internships, connect with as many people as possible who might help you land a job, be willing to work hard and be resourceful–and you’ll be fine, whether or not you know how to build an app or program a computer."

Generalizations ignore particularities. But these particularities are what makes each of our lives what they are. We are not a statistical artifact. Our individual lives will always matter more than generalizations.

You can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something - your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life. - Steve Jobs, American entrepreneur

No comments:

Post a Comment