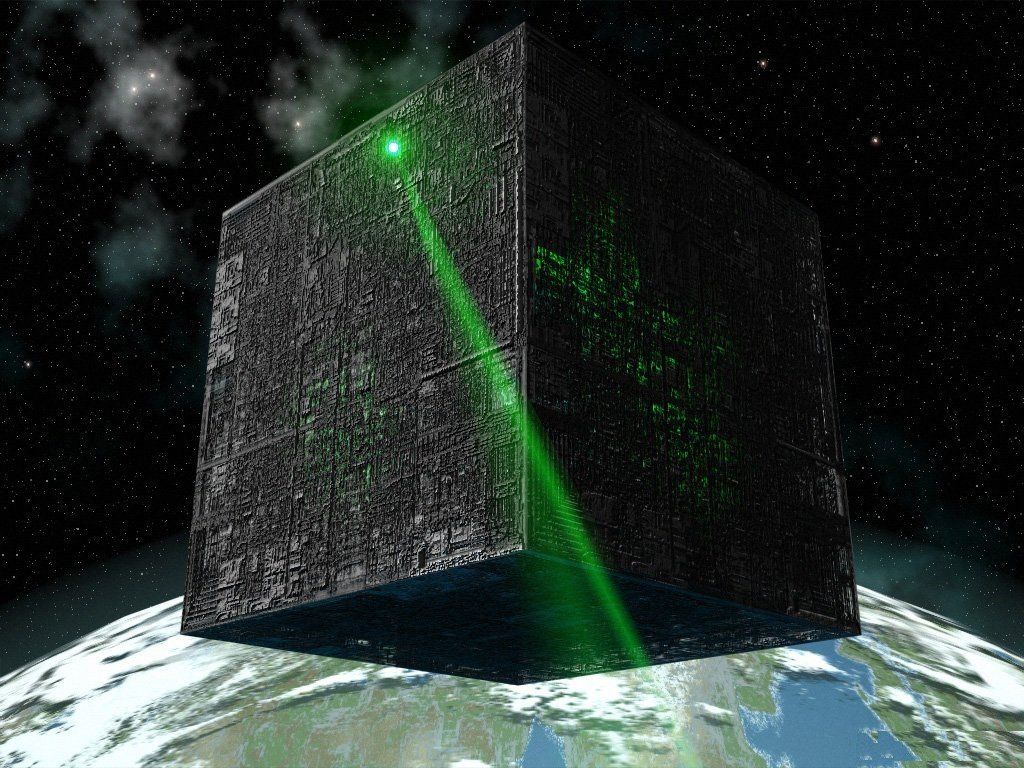

"Resistance is futile."

Last night, in my graduate

The Borg, for those of you who don't know, are a fictional pseudo-race of cybernetic organisms depicted in the Star Trek universe." (source) They are a collective of involuntarily assimilated individuals, linked up into a "hive-mind," which operates at an emergent level above the members, combining the intelligence of each with synthetic components (i.e. computers and other hardware) to create a super-intelligent, nearly indestructible entity. The Borg's capacity to adapt to nearly every changing situation, and to respond without remorse, makes it (them?) the most diabolical enemy faced by The Next Generation's Captain Jean-Luc Picard and his Enterprise crew.

Besides being a specific reference to this Star Trek antagonist, "The Borg" has become a cultural icon, representing the purported outcome of an increasingly wired and connected human species. The concept comes to mind when you imagine hordes of people jacked into their computers, all somehow unwittingly subjecting themselves to some larger force that uses their individual powers towards some inhuman end.

Last night, I encountered this creature, in a graduate Technology in Education (TIE) class I was teaching.

This particular class is a new one for our program, combining elements of another course that was streamlined with some older program content that had been, for a while, set aside. Specifically, the course focuses on the uses of application technologies (or what David Jonassen memorably calls "mindtools") in supporting K-12 student involvement in problem-based learning (PBL). As both the person responsible for creating this "new" course out of the other components, and the first member of our faculty to teach the course, I've been steeped in an effort to make the course relevant and challenging for our students.

I seem to have succeeded in the challenging part. (Relevance, not so much. See below.) Jonassen writes in several of his published articles (including this one) about the importance of having students build models as part of the learning process. "Model building is a powerful strategy for

engaging, supporting, and assessing conceptual change in learners because these models scaffoldand externalize internal, mental models by providing multiple formalisms for representing

conceptual understanding and change." Because I want the TIE students to learn not only how to focus learning on problems, but also to make these learning experiences meaningful (in the sense of "meaningful learning" employed by Ashburn and Floden, among others, which places "content centrality" among the key criteria of meaningful), I decided to combine the use of mindtools to build models with the instructional approach of problem-based learning, and have asked my TIE students to build PBL mini-units for their K-12 students in which they pose problem scenarios that require the use of models to understand the scenarios (or systems) well enough to gain the sophisticated understanding that can support well-reasoned solution.

(Note: another big challenge I have faced in this course has been to adequately explain the concept of "system" in a way that makes sense to my students, but that's a problem to be discussed at another time.)

In other words, I have combined Jonassen's third edition of Modeling with technology : mindtools for conceptual change with the much more teacher-friendly second edition of Problem-based learning: an inquiry approach by John Barell. My theory is that adding modeling into PBL will "jack up" the learning that will occur in these units, and that the TIE students will gain a better understanding of the importance of writing units that pay specific attention to their students' conceptual change and the ways that technology can support that.

I still believe in that theory, and I'm not yet ready to abandon it, but I must tell you it's been a challenge. First off, there is the enormous challenge of getting my graduate students to read the books. Few of them have shown a capacity or a desire to refer to either of the assigned books during class discussions or in their blog posts.

The Jonassen book is, admittedly, somewhat challenging in an intellectual sense, both because the concepts he is presenting are intrinsically hard to comprehend (and sufficiently far from most people's prior experiences in classrooms that they seem foreign) and because the examples he chooses to mention in the book are insufficiently described or inappropriately complex for these K-12 teachers; not to mention that the book seems overly redundant (especially on a superficial reading), as if Jonassen is forced in the book to repeat the basic concepts again and again either to reinforce them in diverse contexts or, perhaps, to fill out the book. So I empathize with the complaint that the book is difficult reading, although I don't find myself sympathizing with the decision by some to skip it.

However, in merely skimming or even avoiding a careful read of Jonassen, my students may be missing some important ideas. Problems are mentioned early in the book as potential motivations for modeling:

To successfully solve virtually any kind of problem, the problem solver must mentally construct a problem space. A problem space is mentally constructed by selecting and mapping specific relations of the problem (McGuinness, 1986). Use of modeling tools to create visual or computational models externalizes the mental problem space of a learner. As the complexity of the problem increases, producing efficient models of the problem becomes even more important (McGuinness, 1986).

This is helpful, but the connection between problem-solving and modeling isn't carried throughout the rest of the chapters. While Chapter 6, "Modeling Problems," does carry the concept forward, especially in the following passage:

"Among the most important skills in solving a problem is the ability to construct some sort of internal representation (conceptual model) of the problem (i.e. the problem space). The richer and more accurate a learner's representation of the problem, the better the learner's solution is likely to be. Personal representations of a problem server a number of functions (Savelsbergh, de Jong, & Ferguson-Hessler (1998):

- To guide further interpretation of information about the problem

- To simulate the behavior of the system based on knowledge about the properties of the system

Jonassen goes on to decry the typical "problem" encountered in school, which can usually be solved by using a previously-derived formula and plugging in the right values. When students do that, Jonassen argues, "they do not construct any qualitative understanding of the content they are studying."

- To associate with and trigger a particular solution schema (procedure)"

Chapter 6 also includes several examples of problems and the models that could support their resolution. Unfortunately, these examples do not sufficiently make the case that the creation of the models was a central ingredient in the resolution of the problem, perhaps because the focus of the chapter is on the models themselves rather than the problems that may have motivated their creation. Indeed, the models seem either gratuitous or inscrutable, a problem made worse by Jonassen's reliance on rather complex technologies that are completely unfamiliar to my students such as expert systems, systems analysis tools, and high-end visualization tools. (This lack of familiarity with these tools is exacerbated because they are not available in my university's computer lab.) What's "modeled" in Chapter 6, perhaps unintentionally, is that mindtools are really only helpful for solving problems in advanced subjects and grade levels.

The Barell book, by contrast, is easy reading, full of detailed K-12 examples and useful tables and questions for reflection. But, unfortunately, Barell barely mentions technology and treats modeling as something the teacher does (showing the students how to go about their inquiries), rather than a tool that students might use. Barell does discuss the importance of having students make observations and analyze a problematic situation, but his examples tend to be quite concrete, with the analysis primarily involving generalizations or deductions from facts rather than the synthetic or inductive thinking necessary to construct a model of an ill-structured or barely understood system. As a practical guide to (non-technological) PBL, the Barell book is exemplary, but as a support for changing teachers' understanding of how technology can be used effectively to support higher-order thinking, it's pretty useless.

So, I have been struggling to find a way to "fit" the two books together. This has involved considerable searching on my part for examples of systems that can be modeled using available tools such as Excel and Inspiration. My goal has been both to show the usefulness of modeling and to show that these tools can be used for more than just recording data or brainstorming as part of a KWL.

Unfortunately, the more examples I find (or create), the more frustrated some of my students have become. This frustration burst into public view last night in my class, when one of my students, who is a computer lab teacher in a suburban Catholic school, complained that my examples of how "concept mapping" can be a much more elaborate and rich process than the creation of a simple bubble chart simply weren't relevant to her struggles to construct an effective problem-based mini-unit for her second graders.

This student had turned in a draft mini-unit in which her students would be presented with a problem scenario involving pollution in Lake Michigan and would work as a class to build a concept map of their preexisting knowledge of pollution, and then do some online research to "fill in the concept map" before returning to the larger group to combine what they learned and discuss the implications. The draft of the mini-unit plan that the student had turned in was very short and somewhat "vague" (as she admitted), and I had responded with a set of questions and concerns. I didn't see how the problem scenario she mentioned (pollution in Lake Michigan) related to the whole-class creation of a concept map about pollution in general. In her draft, she also didn't mention the grade level of the students, or include a timeline of activities, which meant i was responding a bit blindly. "I am not at all sure that the students' 'modeling' will actually help them to learn," I wrote. I ended my response with this sentence:

Clearly, my emailed reaction to the draft had left this student feeling upset, and my subsequent discussion of the elaborate concept maps I found (and my explicit denigration of the typical "bubble chart" produced in many school situations) exacerbated those feelings. She (understandably) wanted more guidance about what would be acceptable in her situation.I’d like you to think about these questions and, most importantly, figure out a way to have the individual students actually DO modeling in a way that helps them to solve a specific problem that they are presented with.

As we discussed her frustration (and she fought to control the tears that came to her eyes), I learned that her unit was intended for second grade (!) and that she was facing the challenge of doing this unit in the 40 minutes per week (!!) that she saw her students, and that she expected the unit as it was written to take at least a month. Couldn't I give her an example of what I would suggest that she do in that situation, rather than continue to describe examples that seemed completely out of reach?

I admitted to being flummoxed by the challenge she faced in effectively using problem-based learning with technologically-supported modeling with second graders whom she saw so infrequently and for so little time. I also admitted being frustrated in my efforts to offer concrete, specific examples of lesson plans involving both PBL and substantive use of model-building by students at such a young age. I reminded her that my K-12 teaching experience was at the high school level (chemistry and pre-calculus), and that I didn't know much about teaching young students. She acknowledged the challenge that I faced, but again stated her expectation that as the teacher of this class I had a responsibility to offer her more specific guidance and support. I promised to come back next week with some more relevant examples. One student very helpfully suggested that good examples of the use of concept mapping in the early elementary grades could probably be found by looking for Kidspiration examples at the http://inspiration.com web site. (I am hoping to use some of those examples next week.)

What happened next left me feeling sad and confused. A few other students seemed to jump at the chance to criticize my teaching abilities and lack of relevant prior experience. How could I be so critical of the common practices in elementary school classrooms when I myself had not only never faced those challenges but could not describe exemplary lessons that incorporated both PBL and effective use of mindtools. These comments seemed somehow coordinated, as if the students had discussed this criticism of me earlier amongst themselves, and were prepared to bring it up as a group. I noticed that a few of the students, who seemed disconnected from the ongoing discussion, had their heads buried in their laptops, typing away. At least one of those was laughing at something she was reading on her screen.

Not wanting to allow the class to deteriorate into a out-of-control bitch session, I quickly pulled myself together and moved on to discuss an example I had created of how a database might be used to support a problem-based scenario involving the causes of war. Many of the students seemed engaged by this example, while a few others seemed, to me, to have already decided that nothing I could say in class that night would be helpful.

As I wrapped up the database discussion, and packed up my things to leave, I found myself swimming in a whirlwind of emotional and intellectual reactions to what had just happened. I certainly deserved to be called on the carpet for my inability to provide specific early elementary examples of what I wanted the students to do in their mini-units. I felt badly for the student who had gotten so upset. I wondered to myself (not for the first time) if my lack of elementary school teaching experience meant that I should get out of the business of trying to teach teachers how to use

As I drove the 34 miles home, I was able to process some of those feelings. It was really very brave of that student to confront me with the fact that my examples seemed irrelevant to her (and others') situation. Her courage to bring it up would serve as an incentive for me to work harder to find and to describe examples of what it was I hoped the students would do. Excellent teaching, I reminded myself, always means paying attention to feedback from students and appropriately adjusting one's actions. I could forgive myself, especially, since this was the first time this course was taught, and even though I had (typically) erred on the side of setting my expectations too high, the students would probably benefit in the long run, and I could show that that I'm continuing to learn, as well.

Yet despite these calming thoughts, and the resolve to rise to the challenge that this situation had presented, there remained a core feeling of anger about what had happened. Gradually, the focus of that anger became clearer. It wasn't that the student had raised her objection to my approach, or that other students expressed their similar frustrations. Nor was it the feeling that they had discussed this amongst themselves earlier. Indeed, I consider that a good thing, because it illustrates our faculty members' pretty successful effort to form our students into learning communities as they progress through the program.

What continued to bother me was the way that some of the students had their heads buried in their laptops while the confrontation unfolded and, especially, that laughter that seemed such an inappropriate response to the feelings being expressed by some of the students and by me. What was going on there?

Suddenly, as I thought about this, I remembered what had been going on in the classroom earlier that evening when I arrived. Most of the students have an earlier class together, and they typically socialize and often share food during the short break between the classes. They are all always there when I walk in, and tonight was no exception. When I walked in, what had been a lively level of chatter suddenly stopped. As I spent a few minutes uploading a file to my web site that would be used in the first activity of the evening, I had looked around the room, and wondered at the cessation of conversation. "While I do this, carry on with what you were discussing when I arrived," I said. The words "chat" and "talk" and "contact" emerged. "You've been voted off the island," one called across the room to another. I asked a student what was going on. "We're all getting connected to

I had thought nothing of this when it had happened. I'm always supportive of my students teaching each other about new technologies. This is what makes our cohort system effective; the more communication, the better. But now, as I drove home and I thought back on the start of class three hours earlier, I realized what had been going on later in the class. Those students with their heads buried in their computers--the ones seemingly disconnected from the class, even laughing out loud at what they were reading or typing--were involved in a backchannel online chat, presumably about me and my response to the expressed frustration of some of the students. The laughter? It seemed to be at my expense.

I realized that the students' decision to gather together on Talk wasn't just about bugging each other at work the next day: it was about having a group discussion, during class, about something they preferred not to discuss openly in the room. This also explained, I realized, the degree to which some of the students had misunderstood my oral instructions about the earlier class activity. The students were distracted by their online chat, and it had been going on the whole time.

As I thought about this, and tried to connect what I'd actually experienced in class with my imagined portrayal of what the students were doing on their computers, I was taken back to a talk that I had given the previous night, in Second Life, on the topic of filters and schools. I had been vehement in saying that schools needed to find a way to embrace new technologies, such as social networks, blogs, and yes, even, online chat, if they were to adequately prepare their students for the challenges of the

This morning, when I woke up, I went online and did some searching for topics related to "online chat" and "during class" and "distracted." While most of what I found painted a rosy picture of what chat, as a backchannel to classroom activities, could add to student engagement and learning, I also found numerous examples of professors who were frustrated that students seemed more involved in their IM conversations, or

I honestly don't know what the students were saying to each other in chat during last night's class session. For all I know, the laughter that came from at least one of the distracted students was a reaction to something a friend of hers had posted on

1 comment:

Hey Dear Candidate, looking for free creating for free

For free website creation services, A place where you can Create Free Website no designer, no programmer, no hosting space is requires just only in three easy steps you can create your own website free of cost.

Post a Comment